The UK is to rejoin the EU’s flagship scientific research scheme, Horizon, the government has announced.

UK-based scientists and institutions will be able to apply for money from the £81bn (€95bn) fund from today.

Associate membership had been agreed as part of the Brexit trade deal when the UK formally left the EU in 2020.

However, the UK has been excluded from the scheme for the past three years because of a disagreement over the Northern Ireland Protocol.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said: “With a wealth of expertise and experience to bring to the global stage, we have delivered a deal that enables UK scientists to confidently take part in the world’s largest research collaboration programme.

“We have worked with our EU partners to make sure that this is the right deal for the UK, unlocking unparalleled research opportunities, and also the right deal for British taxpayers.”

Thursday’s announcement also states that the UK will associate to Copernicus, the EU’s £8bn (€9bn) Earth observation programme. Britain will not, however, be rejoining a nuclear research alliance known as Euratom R&D, although there is an agreement to cooperate specifically on nuclear fusion.

In a press release, the European Commission said that the decision would be “beneficial to both” and stated that “overall, it is estimated that the UK will contribute almost €2.6bn (£2.2bn) per year on average for its participation to both Horizon and Copernicus.

The scientific and academic community has welcomed the news of Horizon association.

Chief Executive of Universities UK, Vivienne Stern, told the BBC there would be a “unanimous sigh of colossal relief” from scientists which would allow them to work across geographical borders by drawing funding from a common pot.

“I was looking at one project which is mapping the human brain – a colossal project involving 500 researchers in 16 countries – it’s been going on for 10 years. The scale [of the projects] is impossible through national funding mechanisms.”

And Nobel Laureate Sir Paul Nurse, who has been one of the most vociferous voices in arguing to rejoin, added: “I am thrilled to finally see that partnerships with EU scientists can continue. This is an essential step in re-building and strengthening our global scientific standing.”

The UK’s association to Horizon was agreed in principle as part of the Brexit Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA), but the issue then became bogged down in the dispute about the Northern Ireland Protocol.

The European Commission refused to allow membership of the science and Earth observation programmes until the UK fully honoured its negotiated commitments.

The Windsor Framework, agreed last February between Brussels and London to fix their differences over Northern Ireland, also had the effect of unlocking the associations. The past six months have seen both parties negotiating the financial arrangements of membership.

These haven’t yet been fully disclosed but will require the UK to be making monetary contributions consistent with the size of its economy relative to the EU-27 bloc. There are performance provisions if UK scientists win “too many” or “too few” grants, but these are not materially different from the thresholds written into the TCA, Brussels officials told the BBC.

UK scientists were always the big winners in the grant process for past Horizon programmes, jostling for top spot and sometimes outcompeting the other European science superpower – Germany.

The delay and uncertainty in agreeing association has seen a drop in applications from UK scientists to work on European projects that were underwritten by UK government money.

The impasse also led some EU nationals working in the UK to take their research back to their home countries or to other EU states. In addition, British researchers who had been in leadership roles in some big, long-running projects were forced to step down.

Ministers and science officials will now hope the new deal will re-energise the sector, encouraging UK researchers to reassert their prominence in European science.

Sue Ferns, from Prospect, the union representing many workers in the research sector, said: “The UK rejoining Horizon is welcome but long overdue and we are now playing catch-up as we try to make up for lost time. Ministers now need to guarantee sustained investment across the sector – scientific expertise is critical to meeting the generational challenges we are facing.”

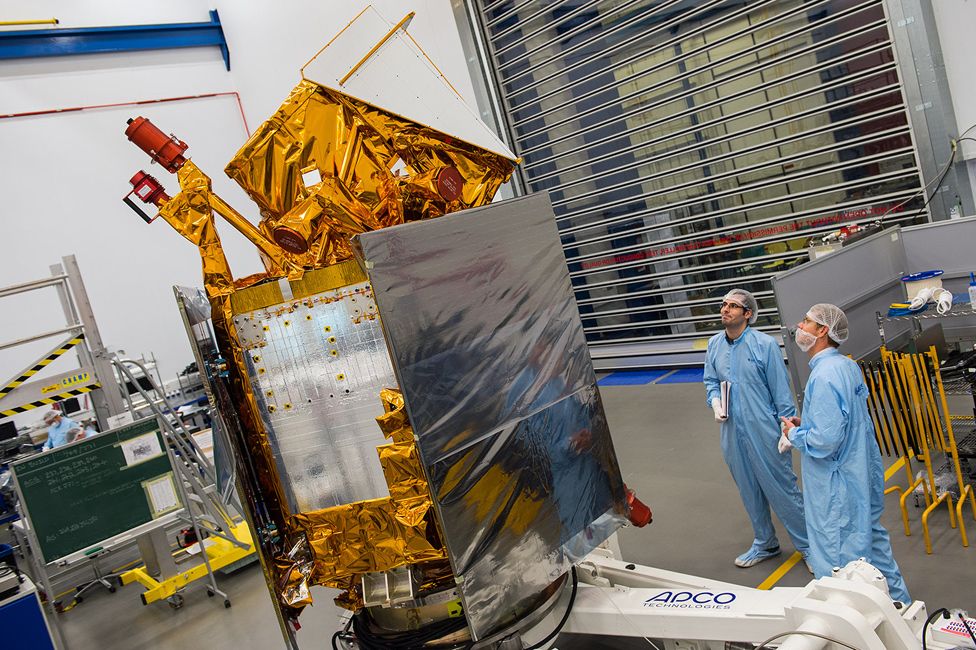

The Copernicus association keeps UK scientists at the forefront of climate research, and permits Britain’s aerospace industry to bid for satellite contracts worth hundreds of millions of euros.

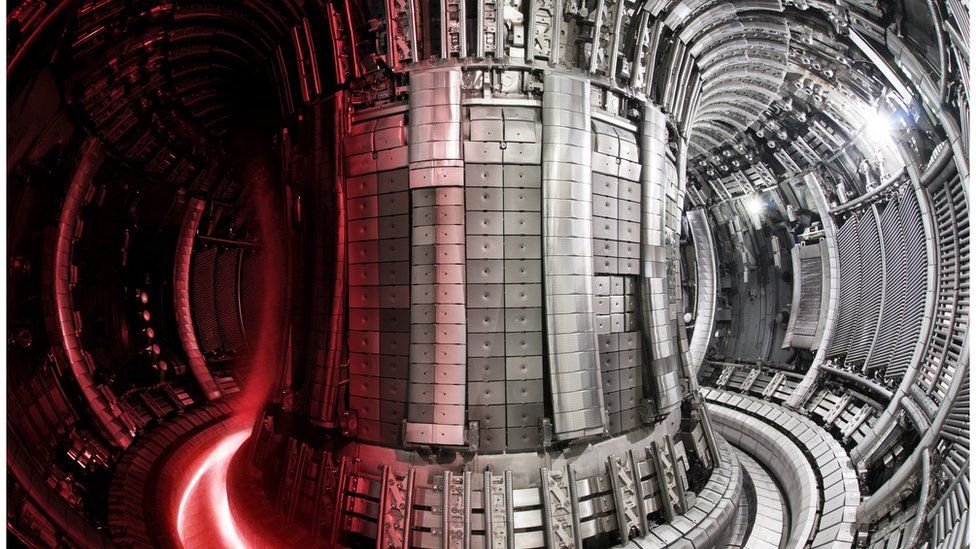

Nuclear fusion

The one EU programme the UK might have joined but will not now pursue is Euratom R&D.

This concerns research and training in areas such as nuclear safety, radiation protection and waste management.

Although association was permitted under the TCA, the London government came to regard it as poor value for money.

Instead the UK will institute its own programme focussing on nuclear fusion – the science of trying to extract energy by forcing together light atomic nuclei.

It will involve international collaborations. After all, the UK still hosts Europe’s leading fusion lab – the Joint European Torus (Jet) in Oxfordshire.

The alternative programme will be backed by £650m up to 2027, the UK government says.

What the associations do not change are the restrictions/requirements on EU or other foreign national scientists wanting to come to the UK to do their research; and vice versa.

There is no “freedom of movement”. Scientists wanting to come to the UK need visas, which are among the most expensive in the G8.

Michelle Donelan, the secretary of state for science, innovation and technology, defended the government’s position on immigration on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

“It’s important that we look after the interests of the British taxpayer, that we make these decisions to try and control immigration. That was the pledge that we made in our manifesto, and… I think we should be determined to keep that pledge and to work hard to deliver it,” she said.

“But at the same time, we do want to be attracting the best talent from around the world to work here on agendas like science and technology, because we are on track to become a science and tech superpower by 2030.”

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer welcomed the UK’s return to Horizon but lamented the delay.

“I think there’s a sense that we’ve lost two years, that this should have happened two years ago and that’s a big loss,” he said on a visit to Macclesfield.